Photo by Gage Skidmore

Just after the election, Joe Biden claimed a mandate:

“They’ve (voters) given us a mandate for action on COVID, the economy, on climate change and systemic racism. They made it clear they want the country to come together not continue to pull apart.”

This is nothing new. Regardless of the circumstances, victors often invoke the mandate narrative. After losing the popular vote in 2016, Donald Trump declared a “massive landslide victory in the Electoral College”. Following relatively close re-election contests, George W Bush and Barack Obama asserted their policies were vindicated.

Emboldened by victory, presidents are effectively arguing that Congress should grant them deference in executing their agendas. The logic is simple enough: Let the new President carry out the policies that he promised during the campaign. After all, the people voted, and Joe Biden won. It’s the Democrat’s turn.

But what is a mandate, and can Biden legitimately claim one?

Mandates

A mandate is central to democratic politics. It connects policy to the wishes of the electorate. This is what democracy is supposed to do.

Noted democracy scholar, Robert A Dahl observed that elections can be interpreted as policy mandates: “a clear majority of voters preferred the winner because they prefer his policies and wish him to pursue his policies.” Therefore, newly elected presidents, buoyed by the will of the people, assume the authority to carry out campaign promises.

Research shows a key factor in the president’s success with Congress is in fact public support. Mandate claims, especially those after landslide elections, can therefore be effective in influencing legislative behavior. And, during the first few months of the term called the “honeymoon ”, Congress does seem to respect the mandate claim.

But not all mandates are equal. And not all newly elected Presidents enjoy a honeymoon.

Because they matter, mandates are scrutinized and challenged by the opposition. To be sure, claims are more persuasive if the candidate wins by overwhelming popular vote margins and the electoral college vote totals are extraordinary. But for closer contests, opponents will argue that the newly elected president has no warrant to call on Congress to fund campaign promises – with a slim margin of victory and a divided electorate. The White House, meanwhile, will counter that the election triumph demands that Congress act on campaign promises thereby validating the people’s choice.

Let’s examine 2 measures that help determine whether Biden can justifiably claim a mandate.

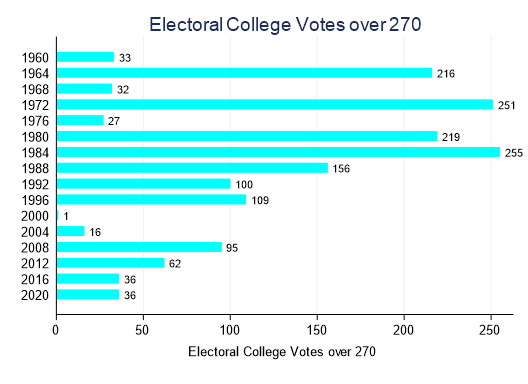

Electoral College Votes

The chart below depicts the number of electoral college votes that exceeded the majority threshold required to win – over 270. Three points are noteworthy. First, several elections produced electoral college landslides, as the winner surpassed the 270 threshold by well over 100 votes – examples 1964, 1972, 1980, and 1984. Notice, however, since the 1990s, those electoral college margins are much tighter. In short, our presidential elections are increasingly competitive.

Second, the 2000 election shows just how close a presidential election can be. George W. Bush surpassed the electoral college threshold by one vote. Four years later, Bush won another squeaker, edging John Kerry by less than 20 electoral college votes. Besides 2000, the 2004 contest was the closest electoral college margin in decades.

Finally, Biden’s 306 electoral college votes gave him 36 more votes than required. That figure exceeded George W. Bush’s electoral college margins in both 2000 and 2004 and surpassed John F. Kennedy’s total in 1960 and Nixon’s in 1968.

Yet, ironically, Biden’s total matched Trump’s 2016 tally over Hillary Clinton. Biden’s Electoral College totals thus put him in noteworthy historical company – among the closest electoral college votes in the modern era.

Popular votes

Electoral college votes can be deceiving. Recall, popular votes and electoral college votes are not equivalent. The 2000 and 2016 election demonstrated the popular vote winner can in fact lose the election.

So, perhaps claims of democratic legitimacy should begin with popular vote totals.

Let’s take a look.

Across 16 elections, the average popular vote margin was approximately 7 million (see table). 1960 was a razor thin victory for John F. Kennedy. Likewise, Richard Nixon edged Hubert Humphrey in a very close 1968 contest. And, while Al Gore won the popular vote by half a million, he did not win the presidency in 2000. Barack Obama’s popular vote margin in 2008 was the largest since Ronald Reagan’s sweeping victory over Walter Mondale in 1984.

Popular Vote Totals and Margins of Victory

| Year | Dem pop vote | Rep pop vote | Disparity |

| 1960 | 34.2m | 34.1m | 0.1 |

| 1964 | 43.1m | 27.2m | 15.9 |

| 1968 | 31.3m | 31.8m | 0.5 |

| 1972 | 29.2m | 47.2m | 18.0 |

| 1976 | 40.8m | 39.1m | 1.7 |

| 1980 | 35.5m | 43.9m | 8.4 |

| 1984 | 36.6 | 54.5m | 17.9 |

| 1988 | 41.8m | 48.9m | 7.1 |

| 1992 | 44.9m | 39.1m | 5.8 |

| 1996 | 47.4m | 39.2m | 8.2 |

| 2000 | 51.0m | 50.5m | 0.5 |

| 2004 | 59.0 | 62.0m | 3.0 |

| 2008 | 69.5m | 59.9m | 9.6 |

| 2012 | 65.9m | 60.9m | 5.0 |

| 2016 | 65.9m | 63.0m | 2.9 |

| 2020 | 81.2m | 74.2m | 7.0 |

Biden’s margin of victory of 7 million appears typical, right on the historical average – though he did receive more popular votes than any other presidential candidate in history. Like his electoral college total, Biden’s popular vote margin makes it difficult to sustain the mandate narrative. Perhaps if Biden’s vote totals had reached pre-election forecasts, a stronger argument could be made. But Biden’s national popular vote margins were short of expectations and margins in several swing states fell notably below projections – and Biden’s defeat in Florida certainly renewed doubts about the forecasting industry.

Bottom Line

2020 was a close election in a period defined by highly competitive elections – notice in the last 16 presidential elections, each party has won 8.

For the six most recent elections, the average popular vote margin was 4.7 million and the electoral vote margin 41. From this vantage point, only Biden’s popular margin of victory appears significant. Using a longer time frame – beginning in 1960, Biden’s electoral college margins are in fact smaller than normal and his popular vote margin average. Neither comparison establishes a Biden mandate.

Biden’s victory does bring an end to the Trump era and signals a return of centrism. During the campaign, Biden argued the stakes were high and the battle was over the very soul of America. Time will tell whether Biden secured the hearts of Americans and whether he can truly hold the middle in the age of partisan rancor and polarization.

Look for part 2, where I evaluate several additional mandate criteria.

Love the post.

A couple of things jump out to me as irregular about the detail. First, would be the dramatic increase in voter turn out in comparison to estimates and past years. A deep dive into the numbers and maybe commentary on probable and speculative reasons behind them would go a long way to understanding the turn out and the results from this cycle.

Does the population both love and hate Trump so much as to provide at 9.3 million vote increase for Dems at the same time as a 7.8 million vote increase for Reps as opposed to 2016. Or, a more intriguing change of +5.7million and +10.9 million respectively over what everyone assumed was the Historic election of the century in 2008.

It is interesting to note that the mainstreaming of politics, perhaps even the creation of celebrity out of our elected officials, has helped to increase voter participation over the last 20 years that far outpaces the population growth in this country. Between 1960 and 2000 the U.S. population grew by 57% but the voting growth was half that number (27%). Over the last 20 years our population growth has slowed to 18% across that period. But, the popular vote numbers have grown by nearly 60% in that time frame.

I would really love to see your perspective on the possible reasons behind what seems to be a election cycle outlier. Or, are we on the other side of some voting related tipping point in our country.

LikeLike

Yes, those are weighty questions and remarkably difficult to answer. At this point, I am uncertain about turnout figures and await more thoughtful and considered analyses — though that will take some time. I suspect this election (and the Trump presidency) will be the most researched area in political science for years to come. I do agree, however, that the dramatic increase in turnout is unprecedented. 2018 turnout did signal that the electorate’s typical pattern of participation maybe changing. Indeed, 2018 set records and appears as a distinctive outlier for midterm elections. Without question, Trump made people care about politics. Those that hated him, and/or those that hated Republicans, cared because they wanted anything but Trump (Republicans) in the White House – so they were truly motivated to participate – that includes millions of party members willing to invest heavily in mobilization efforts. Those that loved him – and/or hated Democrats, cared because Trump represented something they never had – a political outsider willing to attack the opposition and bend/break prevailing norms and standards. So, both sides had much to lose and therefore participation was very high. There is more, of course. State level changes that encouraged greater participation – most notably vote-by mail, a persistently loud and arousing news media, a severe economic contraction, protests, and a ranging pandemic. These circumstances all pointed to higher turnout – at least historically such events tend to focus the electorate and elevate the challenger. Finally, I do think we have reached the turnout summit. Why? Ironically, to much participation can be a bad thing. If well over half the population intensely cares who wins the White House, democracy could be in trouble. This is contrary to contemporary ideas but many early 20th century election scholars properly recognized the thresholds of healthy participation. It’s very difficult to weaken the party duopoly, and the larger political system that encourages it. Yet, intense, consistent, and broad mass participation can threaten both. It can eclipse the safe boundaries of institutionalized participation (voting, protests) and spread into the social and economic spheres. If this happens, elites from both parties begin to moderate — they have the most to lose. The rhetoric is the first to cool. Let’s see what happens. BTW, great questions. And yes, I dodged most of them 🙂

LikeLike

LOL. With those kind of “dodges”, maybe you have a career ahead of you in politics.

I believe that the thing I noticed the most was the extreme rise in political participation as a percentage of the population. I do believe that the health of our Democratic Republic is staked to keeping our elected officials tied more to the actions, and consequent results of their policies as compared to dumbing down the process to popularity only. I don’t want to feel like we are voting in a prom King or Queen every 4 years.

From a novice point of view, I would hope for 3 general changes to our current process: 1 – voting reforms that would require a person to minimally have to be a legal citizen and actually have to engage in the process (Voting should not be too difficult. but, it should also not be too easy – that could be unpacked a bit of course) 2 – Terms limits should be studied and implemented in some fashion for career politicians. Having people in power for lifetimes is not from the original frame-workers intent, except for the supposedly non-political judicial branch. We can rarely trust those that make the rules to not eventually be managed by the attraction to the very power they are responsible to create. 3 – I would promote the idea of a two term max for the presidency, based on a first term of 6 years and 2nd of four. Getting things actually done should be paramount for any party in power. spending a quarter of that 1st term trying to get to 2nd is counterproductive. Current terms result in a 1st term effectiveness period of 3 years and a potential 2 term effectiveness of 7. My suggestion would alter this to 5 years in the first term and 9 over 2 terms. Ultimately it would also lower the collective temperature of a country that is increasingly polarized, in part because of the frequency of election cycles.

LikeLike

Yep, well, popularity contests touch on basic instincts and that has not changed – and will not change. There are safeguards in the system, though right now it is fashionable to talk about reforming those – ie, Electoral College, Senate rules. However, after FDR, the country did pass an amendment that effectively term limited presidents — 22nd. Evidently, what the people want (FDR) is not always acceptable regardless of era or regardless of party in power.

More generally, term limits on U.S. Congress were attempted by some states but the Supreme Court struck down the relevant state provisions – U.S Term Limits, Inc. v. Thornton (1995). However, term limiting state legislators is fairly common and an example of how things may play out if Congress terms were limited – one problem I see is that congressional staff and the federal bureaucracy become even more important players when politicians have less experience. Your three points are intriguing, and make good sense from the “experience” perspective. Certainly, a position as complex and dynamic as the President could use a few more years to effectively “season”. The nation would likely benefit from the added experience. And, as you pointed out, presently half the first term is devoted to preparing for the next election — same thing could be said about Congressmen/women. In sum, elections are increasingly impacting governing.

Personally, I find it difficult to square the twin arguments advancing removal of the Electoral College when we also term limit the president. The major thrust of removing the Electoral College is everyone’s vote should count equally and the popular vote winner should move into the White House. In short, reformers want a greater role for the people’s preferences. Well, then why ignore (undermine) the people if they want to elect a president to a third term? Why do we trust the people’s will for 8 years and nothing more? Most historians and political observers rank FDR as a top 5 president – its not unanimous but close. Today, we would term limit FDR.

Finally, your point about the frequency of elections is spot on! There is such a thing as election fatigue – I suspect its especially chronic in California 🙂 This is one reason why I think turnout will drop in the coming elections. Every election, we are told the world will literally change if one president or the other is in office. Yes, I agree things will change. But, the stakes are not as high as cable shows lead us to believe. Turns out Trump did not start a war with North Korea and Biden is not senile. I wholeheartedly agree, fewer elections and having more time between them, would drop the temperature.

LikeLike