credit: Rayne Zaayman-Gallant / European Molecular Biological Lab

In the spring and summer of 2017, Minnesota experienced the largest outbreak of measles since 1990. More than 8,000 people were exposed, 500 stayed at home because they were potentially infectious, and 22 people were hospitalized. Seventy one cases were among people who had not been vaccinated. And 81% of all cases were among Somali immigrants, a group than in 2014 had a vaccination rate of only 42%. A CDC analyses concluded that rates declined due to “concerns about autism, the perceived increased rates of autism in the Somali-American community, and the misunderstanding that autism was related to MMR.”

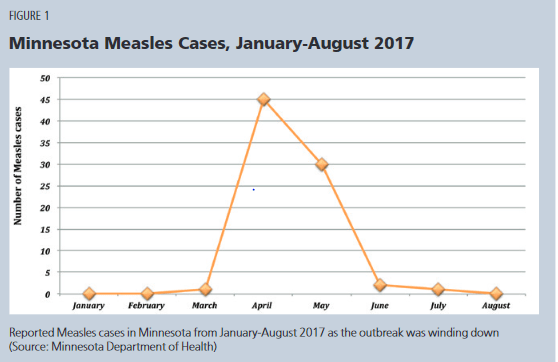

Cases spiked in the spring but by June public health officials were able to contain it. By August, state health officials announced an end to the outbreak.

The Minnesota outbreak offers several lessons

First, high vaccination rates among the Minnesota population protected most people and checked the growth of the virus. For measles, the desired vaccine rate is 93% . Yet high statewide averages concealed much lower vaccination levels in certain regions, among specific groups. The Minnesota case demonstrates that a highly contagious but vaccine preventable virus like measles is very effective at finding the unvaccinated.

Second, amid the outbreak, vaccine skepticism deteriorated. The graph below shows that as measles cases peaked in April and May, MMR vaccine doses administered – especially in the hardest hit parts of state, increased dramatically. Compared to the previous year, thousands of more doses were administered. Since 2017, Minnesota has had only 2 confirmed cases of measles.

Anxiety about a disease seemed to overwhelm misinformation about vaccines. The outbreak threatened many of the unvaccinated – particularly those in the impacted region. Vaccines transformed from a potentially hazardous substance to a welcomed remedy. Vaccine skepticism may not be so deeply rooted after all.

Third, in 2000, the World Health Organization declared measles eliminated from the United States. But international travel reintroduced the disease and, as Minnesota demonstrated, lower vaccination rates contributed to local outbreaks.

In 2019, New York and Washington declared public health emergencies in response to significant measles outbreaks. Clark county Washington was the epicenter and considered an anti-vaxxer hot spot. Most cases were children under 10. The Washington legislature responded quickly and passed a bill that limited exemptions for the MMR vaccines and children could not attend public or private school without proof of vaccination or exemption records.

In New York, a flight attendant developed measles which then spread to several Brooklyn neighborhoods. The mayor ordered mandatory vaccinations and the unvaccinated were barred from public places for 30 days. The New York legislature later enacted a law repealing religious and philosophical exemptions to vaccinations.

In total, 1282 cases occurred in 2019 across 30 states – the largest number since WHO declared measles eliminated from the United States (see graph below). The outbreaks inspired many states to tighten vaccines exemption laws.

Finally, the Minnesota case and others illustrate what may eventually occur with COVID-19. The Minnesota governor and opposition party supported public health officials. Political elites did not send competing messages. Health officials were decisive and broke the chains of transmission. Similarly, in New York and Washington public health officials moved swiftly, beat back the virus, and the legislatures and governors responded with laws that tightened vaccination requirements and refined specific exemptions. In short, local, and state governments cooperated.

The COVID-19 future

Measles was not eliminated – even though 90% plus of the public was vaccinated. For many highly contagious diseases, full immunity may never be realized – eradication may not be possible. Rather, public health strategies will focus on containment. After all, COVID-19 vaccines — while highly effective — won’t last a lifetime. Health experts in fact often discuss a booster or annual shot for COVID-19. Thus, like the flu, COVID-19 likely becomes a constant feature of life, expanding in one season and diminishing in another.

Even if COVID-19 immunization rates surpass 85% to 90% – year after year, that does not guarantee rates would be equal across states or across counties within the states. Some counties will show modest participation while others will reach maximum levels.

This patchwork reflects federalism and the politicization of COVID-19. Future outbreaks are inevitable. The fight against COVID will continue for some time. The virus may recede, temporarily, and then resurface in various regions across the country.

When cases spike, state and local public health officials will act quickly to stop transmission. The news media will report events, the CDC will follow up, health officials will gather data, and state legislatures will scrutinize vaccination laws. Vaccination rates will increase among those impacted and cases decline.

Past measles outbreaks offer a roadmap. The knowledge and infrastructure is in place – and with the latest 2 trillion dollar COVID relief bill, it should receive a considerable influx of resources.

Another great job of bringing historical examples to illustrate present social responses.

Living through this pandemic has not seemed as clear cut as the measles example. The role of denial seems a bigger factor.

LikeLike

History teaches some lessons and others are ignored. as is typically, I suppose. Biggest challenge in the comparative above is the degradation of any faith in our political or scientific community. We have a historic world wide challenge that was met with miraculous response. But, the vaccines are not yet vetting through the lens of longitudinal studies and using modern mechanisms like the mNRA delivery system that are outside of our collective public experience. That in itself is more exciting then worrisome; as it portends future rapid developments to fight other infection diseases.

Having said that, when we get nothing but mixed messages from politicians and the scientific community about everything from masks to schools to surface contact to social distancing to lock-downs to the statistics on infections and hospitalizations, how are we to believe anything.

We had candidates stating they wouldn’t take an shot advocated by Trump, that abruptly change their tune upon entering office. We have mouthpieces for the NIH and the Trump and Biden administrations unable to depoliticize answers to simple straightforward questions, and suggesting that masking and distancing must continue, vaccinated or not. This is all while the CDC messaging flip flops weekly and the WHO investigative inquiry into the COVID-19 origins is headed up by the President of the same EcoHealth Organization that helped fund research into increased transmissibility at the Wuhan Center for Virology.

I other words…….Who to believe anymore. Ultimately, most people will calculate their desire for vaccination based on their level of tolerance to risk and their desire to participate in societal norms that will assuredly be requiring proof of protections.

LikeLike

Yep, a frustrating year -without question. And a year that exposed severe weaknesses in our political system. It is entirely to polarized – lacking the capacity to shed partisanship and offer a proper frame to confront the present challenges. Rather, as you observed, what we experienced was one of the most divisive electoral contest in decades – which began with the impeachment (second) of a president. A period characterized by mixed messages and, at bottom, the motivation to win an election – above all else. Parties (and by extension politicians) do not educate the population, conquer a pandemic, nor even effectively govern. Parties are built to win. After the election, governing is an entirely different matter. A pandemic during a historic election year would always end badly.

However, the larger system which included a private-public partnership produced an unbelievable feat in record time. And, now, despite all the political rancor, the US is doing comparatively well in the administration of the vaccines.

The entire episode demonstrates the patience and composure of the American people. Though the national press often points to groups of Americans that do not meet some predetermined ‘expectation’ – whether it be a behavior or attitude – the political class – and elites generally – often failed the most basic tests. As elite rhetoric – and indeed panic swung widely back and forth, the anchor was the American people. The conflicting messages, the high uncertainty, the school closures, the lock-downs, the protests, etc, through it all, the people stayed solid.

This observation dovetails well with your final observation: “Ultimately, most people will calculate their desire for vaccination based on their level of tolerance to risk and their desire to participate in societal norms that will assuredly be requiring proof of protections.”

I agree. No-one is mandating the vaccine. The messages often conflict – but that’s always been true in political affairs. The decision is a matter for individuals and families to decide – at least for now. Most will get vaccinated – some will not – this is true for the seasonal flu and true for the measles. There will be exceptions and states and local governments will vary considerably on vaccination requirements.

LikeLike